If You Know Your History: The Ties That Bind (Part I)

Football and music are Britain’s post-war belief systems, writes Richard Bowes.

Paul Weller (the legendary frontman of The Jam, not the former Burnley player) once said that music and football are the post-war British belief systems, superseding traditional religions. An astute observation coming from the not-particularly-football-inclined Modfather – and one that is undeniably true.

But why? On the surface level, the differences between the two are stark: music is a creative process with an untethered gestation and limitless possibilities, while football – or specifically a football match – is both tactical and spontaneous.

As the cliché goes, it only takes a second to score a goal that can affect the mood of players, coaches, and managers and may even determine a club's fate. Musicians' spontaneity, barring those that happen in the studio, is limited to the live arena and therefore cherished by a select few.

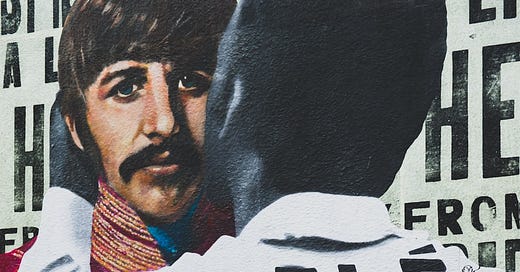

Yet the relationship between the two runs deep. Back in the early 1960s, when post-war Britain was taking shape, pop music, as we understand it, was formulating and The Beatles were conquering all before them while the two teams from their hometown of Liverpool were dominating top-flight football.

Everton were league champions in 1963; Liverpool in 1964 and 1966 with an FA Cup victory sandwiched in between; football’s most prestigious cup competition was in turn won by their rivals the following year.

Merseyside was dominant and, as working-class boys, it was assumed that The Fab Four favoured the most working-class of sports, although only Paul McCartney professed to have any inclination towards a team (in this case Everton), which he put down to family ties.

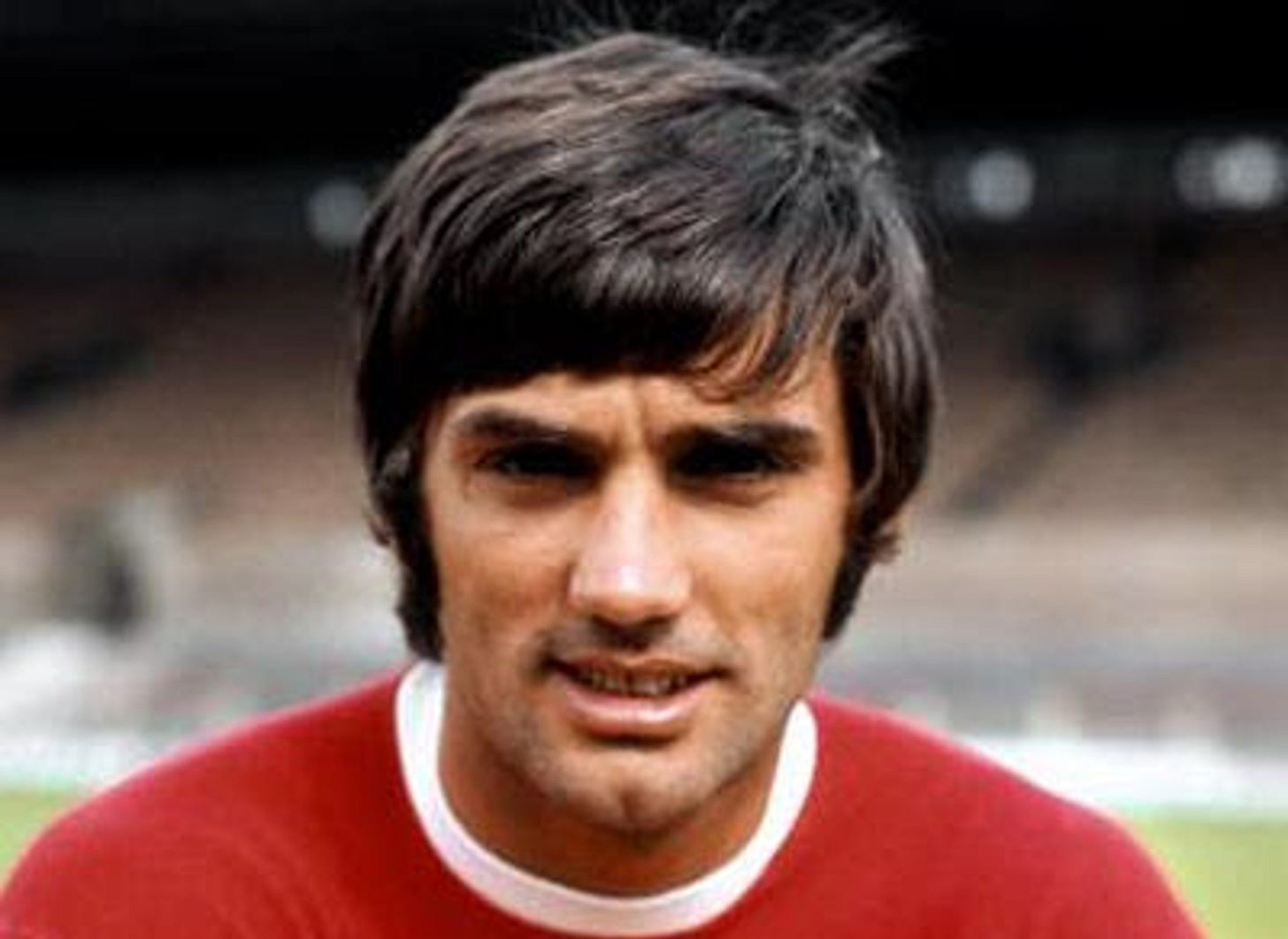

Although a sheer coincidence, the Swinging Sixties’ zenith took place within one week, with the Beatles’ album Revolver – regarded by many as their finest album and certainly their most important – hitting shelves a mere six days after England beat West Germany in the 1966 World Cup final. A few months earlier, a certain George Best had been catapulted to superstar status after scoring two goals in the European Cup quarter-final against Benfica, the Portuguese media dubbing him 'O Quinto Beatle' (the fifth Beatle) because of his mop-top hair.

Best embraced the moniker and the lifestyle, becoming the first ‘rock star footballer’ – namely down his drinking, womanising, and celebrity status – although the seeds had already been sown with an appearance on Top Of The Pops one year earlier. Meanwhile, back on Merseyside, Gerry and the Pacemaker’s version of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ was adopted as a terrace anthem, most notably by Liverpool F.C. but also by Glasgow Celtic.

The ties continued to strengthen throughout the 1970s, which saw the dawn of the dreaded ‘Football Song’.

The first of its kind was ‘Back Home’ by the England national team in 1970, but the music industry (equally aware of the success of the Christmas ‘Novelty Single’) saw the potential and – as was its wont – began exploiting it.

Alongside classic Glam Rock singles like ‘Get It On’ (T. Rex) and ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’ (The Who) sat ‘Good Old Arsenal’ in 1971, while the following year saw ‘Leeds United’ take its place in the Hit Parade next to the likes of Elton John’s ‘Rocket Man’ and ‘Starman’ by David Bowie.

Some of these songs have aged well. Others, not so much.

On and on it went, mainly (if not exclusively) in the lead-up to the FA Cup Final. 'I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles' by West Ham United was a hit in 1975, as was 'Ossie's Dream (Spurs Are On Their Way To Wembley)' in 1981. And lest we forget (no matter how hard we try) ‘Diamond Lights’ by Glenn & Chris – who really missed a sitter by not dubbing themselves Hoddle & Waddle – in 1987. Not content with offending everyone apart from the fans of two specific teams every May (or every four years for the national team), even individual footballers were getting in on the act.

Rock music reached a decadent peak in the 1970s, with the likes of Led Zeppelin and The Who realising venues could not satiate the sheer demand from fans willing to part with hard-earned cash.

While the former band – whose singer Robert Plant is a proud fan of Wolverhampton Wanderers, and later even became Club President – opted to play stadia in the United States, Roger Daltrey and company delighted fans in southeast London with a handful of gigs at Charlton Athletic's stadium The Valley, at the time one of the largest Football League grounds in Britain.

Reasonably, it was surely assumed – and correctly so – that the sound of a football crowd singing and the sound of a gig-going crowd belting out from the terraces were much the same.

Elsewhere, after performing at Vicarage Road, Elton John – with money to burn – bought his beloved Watford F.C. in 1976 and appointed himself chairman, with the most famous images from his tenure occurring in 1984, when Watford faced Everton in the 1984 FA Cup Final, as he was caught on camera in tears during ‘Abide With Me’.

Although there were few tangible links between punk and football (barring elements of hooliganism which were tenuous), the ‘Do-It-Yourself’ ethos did translate to the beautiful game in one way: fanzines.

While fanzines had been in production for several decades (Merseybeat from the 1960s being one of the first examples), the punk movement of the late 1970s inspired music fans; if one did not need to be a trained musician to make punk music, one did not need to be a trained journalist to write.

And so, where music went, with fans equally as enthusiastic, football followed. The first of its kind was The End, produced by Liverpool fan (and founding member of The Farm) Peter Hooton in 1981, followed by the legendary When Saturday Comes five years later – which is still thriving today.

Although the defining feature of football in the 1980s was hooliganism, towards the end of the decade things began to change, once more influenced by the music scene.

A new form of music – Acid House – was the new soundtrack to the underground galvanized by a new, widely available drug: ecstasy. As so often happens, once one gathering of people (those embroiled in this new, exciting form) is influenced by a drug, others follow, and once football fans started taking the pills, the trouble at football grounds subsided – but not enough for Thatcher to gleefully apportion blame on fans after the Hillsborough Disaster in 1989.

Football and music coalesced once again in the summer of 1990, through ‘World In Motion’ by New Order, the official song for England's World Cup campaign. The Mancunian group, as part-owners of the Hacienda nightclub in their home city – largely regarded as the key Acid House venue – were something of a left-field choice but the single, complete with the John Barnes Rap, was a roaring success. Sadly, the original idea for the song (‘E Is For England’… geddit?) never came to fruition.

England's unexpected success in the tournament united the nation and reinvented football in the eyes of the public after a dark decade of violence and bad press. Paul Gascoigne became a cult hero, respected for his on-field talent, lauded for his relatability (the tears), and laughed at for his off-field antics.

Gazza’s capers became headline news and afforded him the status of ‘rock star footballer’ for a new generation, and bigger changes were to come…

Part II coming soon…

By Richard Bowes